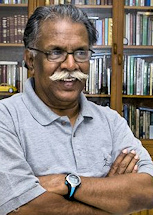

Interview

TB : I have been studying

and writing about South Indian cinema, with particular focus on Tamil

cinema. I would like to describe myself as a Film Historian. I have 3

books to my credit. My career was in civil service. I turned seventy

last month.

TB : In the 1970s when there

was a lot of interest in south Indian studies, I found that this area,

Tamil cinema, had not been touched though it was a major influence on

the life of the people. I decided to study it.

TB : The interaction between

cinema and politics started during the silent era itself. It was one

dimensions of the freedom struggle. It gained momentum during the 1930s

following the Civil Disobedience movement. The Congress party, which

was fighting for freedom used cinema as a tool. It helped in giving the

nationalist struggle a mass basis and helped in political mobilisation.

Cinema house emerged as the first democratic space where all castes and

class could gather irrespective of their station in life. This was a

significant development. During the struggle for Independence from

British rule, the nationalists used cinema as an instrument of

propaganda. Later, film personalities began taking part in direct

political action. Through this two-way involvement with the

nationalistic struggle, cinema evolved as a major political force. After India attained Independence, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, a

radical political party, used cinema for propagation of its ideas and

came to power in 1967. A number of film actors took active part in

politics and were elected to legislative bodies, both at the state level

and at the Central level. All the five chief ministers who have governed

Tamilnadu since 1967 have been associated with cinema. The first two

were dialogue writers and the three who followed were film stars. Other

political parties, such as Leftists, also used film for propaganda. In

the process Tamil films got politicized, playing significant roles in

political mobilization and political activism.

TB : During the freedom

struggle, in the 1930s and 1940s, many film actors took direct part in

political struggle. They courted arrest and went to jail. Some were

delegates to the National l congress annual conventions. Some conducted

passive resistance, like picketing liquor shops and burning imported

cloth. Sathyamurthy, the congress leader, was deeply involved in

cinema. Many other congress leaders supported this aspect of cinema.

Feature films were used for political propaganda. Some Congress leaders

made documentaries and screened them in cinema houses. This interaction

continued even after India gained independence.

TB : It has assumed many

more ramified forms. The Fan Clubs for one thing. The second is the

caste factor. It plays a role in the star politicians’ career. Thirdly

the reach and impact of cinema has increased manifold due to the

television network and DVD revolution. But I would say that the

ideological content of films is less political now. Jean Luc Godard made

a distinction between making political films and making films

politically; what is happening now in Tamilnadu is the second variety.

Since 1967, all the Chief Ministers of Tamilnadu have been associated

with cinema, one way or the other even before they occupied that office.

-

IR

: Let us now tackle

another side of Tamil cinema: its artistic side. According to you, what

is particular in Tamil cinema (its content, its aesthetics…) and

different from Hindi cinema for instance? And what do they have in

common?

TB : Tamil cinema is rooted

in the soil. The landscape, the households and the character are

authentically Tamil. There is an emphasis on the language, particularly

songs. It is the cinema of the Tamils. Hindi cinema is a kind of a

faceless all-India phenomenon. The common features are, as you know,

more of entertainment content, heavy orality (Characters talk a lot),

taking the story along by verbal narration and song-dance sequences as

entertainment components. Both the films are an entertainment pot pourie

without much of ideological thrust. Of course there have been

significant exceptions.

TB : In the fifties one

could talk about Hollywood style and Company drama style. The three

directors from U S, who came to India and made movies here, brought

about this style. Ellis R. Dungan, M. Omelev and M L Tandon. They started

the Hollywood style. Then there was the company drama style by those

directors who had been trained in the drama companies. The Hollywood

style petered out in the late fifties and the company drama style took

over. This was reinforced by the arrival in the 1960s onwards of many

directors from the drama Sabhas (as different from commercial drama

companies these were amateur groups). In recent years there have been a

set of new directors who are not from the drama tradition. This is

refreshing.

TB : You could see features

of a distinct style in film makers like Balu Mahendra and Bala. But I

do not think we can talk about auteur cinema in this context.

TB : Shakunthalai

(1940), Ezhai padum paadu (1950), Yarukkaka Azhuthan (1965),

Aval Appadiththaan (1978), Anbe Sivam (2003). These are

the best among what I have seen. I must add there are many films I have

not seen. These are the best among what I have seen.

TB : Subramaniapuram

(2008), Kanjeepuram (2009).

TB :

A few details about Tamil

cinema. The first film Keechakavatham, an episode from Mahabharatha

epic, was made in 1916. Since then more than 5500 films have been made

in Tamil, with Chennai (Madras) as the centre. Of all the states in

India, Tamil Nadu has the highest exposure to cinema There are 2545

cinema houses in Tamilnadu.

Tamilnadu, a state in India where Tamil language is spoken, is

130058

sq.km in area and has a population of 66

millions. Outside India also, Tamil is spoken by 6 million by people

spread in different parts of the world such as Sri Lanka, Singapore,

Malaysia, Middle East and South Africa. In these countries also Tamil

films are screened A R Rehman who won two Oscars is a product of Tamil

cinema.

|